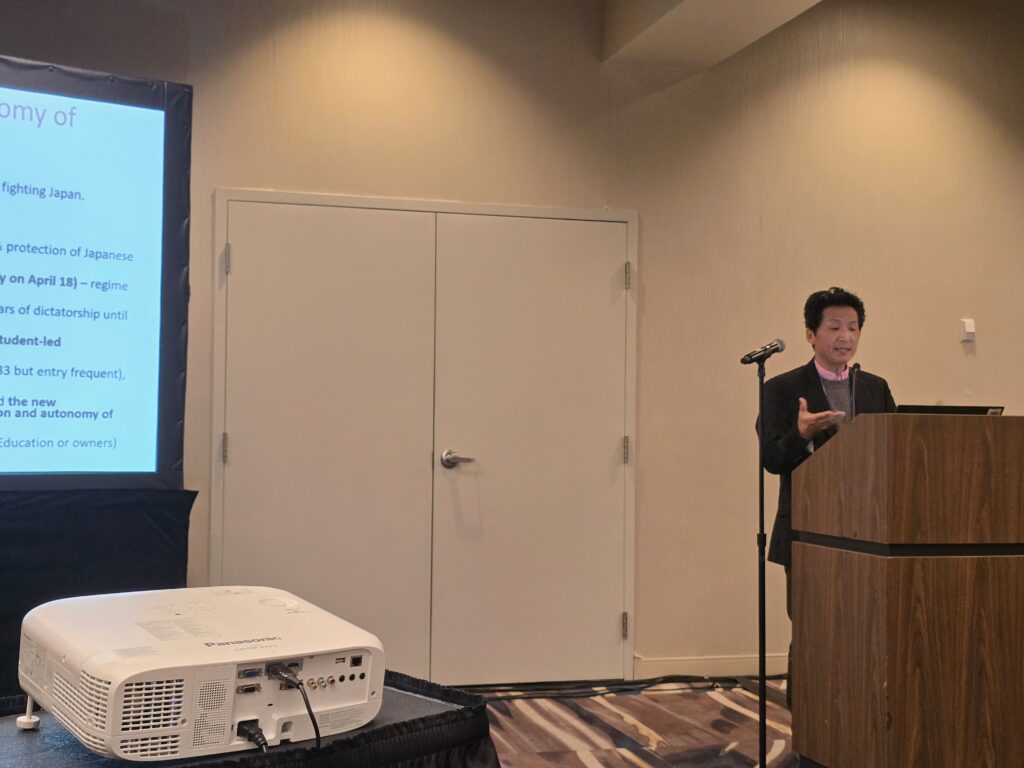

At Association of American Law Schools’ Annual Conference for 2026 in New Orleans, KS Park, the director of Open Net, spoke on January 8 on comparison between a Korean Supreme Court decision that convicted and incarcerated the country’s president for de-funding “left-wing” artists and Harvard v US Department of Human and Health Services which arose out of Trump Administration’s policy of de-funding colleges that maintained diversity, equity and inclusion programs and allegedly were lenient on antisemitism.

The modus operandi for the talk was the uncertainty surrounding the posture of colleges’ independence from government influences. There are two relatively well established constitutional rules: Federal government can set its own funding goals freely (government speech rule). But federal government cannot deny a benefit in retaliation or penalization of freedom of speech exercised outside the funded program (anti-retaliation rule). Are the two rules consistent with each other? What if exclusion of certain content of speech is made part of the funding goal?

That is the issue that confronts the US judiciary deciding on the dispute between Harvard University and the Trump administration, which threatened to cut USD 3 billion in funding unless the school abolish DEI programs and anti-semitism.

In September 2025, a district court did issue a preliminary injunction against the administration, saying that abolition of DEI cannot be made part of the funding goals. The court refused to follow the government-speech precedent that the government can set its own funding goals such as Rust v Sullivan (1991) which prohibited government grantees from counseling abortion as an alternative to birth. The court did not mention Rust at all. Is the refusal sustainable before the US Supreme Court?

The district court does cite the language in Garcetti v Ceballos (2006) where, while ruling that a deputy district attorney/employee was not protected from the anti-retaliation rule for his on-the-job memo, the Court also noted that “expression related to academic scholarship or classroom instruction implicates additional constitutional interests that are not fully accounted for by this Court’s customary employee-speech jurisprudence“. Also, the Supreme Court even in Rust v Sullivan itself noted that:

This is not to suggest that funding by the Government, even when coupled with the freedom of the fund recipients to speak outside the scope of the Government-funded project, is invariably sufficient to justify government control over the content of expression. For example, this Court has recognized that the existence of a Government “subsidy,” in the form of Government-owned property, does not justify the restriction of speech in areas that have “been traditionally open to the public for expressive activity,” United States v. Kokinda, 497 U. S. 720, 497 U. S. 726 (1990); Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496, 307 U. S. 515 (1939) (opinion of Roberts, J.), or have been “expressly dedicated to speech activity.” Kokinda, supra, at 497 U. S. 726; Perry Education Assn. v. Perry Local Educators’ Assn., 460 U. S. 37, 460 U. S. 45 (1983). Similarly, we have recognized that the university is a traditional sphere of free expression so fundamental to the functioning of our society that the Government’s ability to control speech within that sphere by means of conditions attached to the expenditure of Government funds is restricted by the vagueness and overbreadth doctrines of the First Amendment, Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U. S. 589, 385 U. S. 603, 385 U. S. 605-606 (1967).

Is university a special place like a limited public forum where the government cannot restrict viewpoints while some content restrictions are allowed?

At AALS, Robert Post and David Rabban opposed to framing the question this way, arguing that academic institutions should be allowed to engage in viewpoint discrimination and Post argued that even governments should be allowed to engage in viewpoint discrimination in funding the colleges. It seems that they wanted a stronger constitutional theory that protects academic freedom.

In answering this question, Korea’s Supreme Court decision in 2020 may be of significance. President Park Gun-hye’s administration made a list of more than 5,000 artists whom they believe to be “left-wing” and cancelled or withheld subsidies to them. The Korean judiciary top to bottom found that such action is unlawful as the art funding agencies are to be guaranteed their independence. This was done even when one dissenter at the Korean Supreme Court cited Rust v Sullivan (1991)!

What made the Korean decision look effortless was the fact that various statutes related to national promotion of art seemed as if they guaranteed the agencies’ independence from the executive branch.

What if the statutes do not afford such independence? In NEA v Finley, the funding criteria in the statute were amended to include ‘decency’ and the artists’ petition that such requirement constitute viewpoint discrimination was rejected when Mepplethorpe’s photos and the likes were the target of the amendment.

The German principle of statutory reservation requires that all forms of state actions infringing basic rights must be couched in statutes, the statements of law agreed to by the elected representative of the people, not by the executive actions. So, the executive actions of President Park were deemed unlawful because they were eviscerating the statutory mandate: independence of the funding agencies. Of course, this begs the question

of what will happen if the Congress passes the NEA v Finley type of law that requires all federally funded colleges to abolish DEI and anti-semitism.

Such law will be challenged if it happens in South Korea. The Korean constitution of 1987, the product of the epoch-changing democracy movement of that year, newly included a specific provision protecting “autonomy of colleges” as a lesson learned from the role of decades-long student movements and the military junta’s oppressive responses to them such as on-campus command posts. This provision was in addition to the provision of “independence, professionalism, and political impartiality of education”, which has been invoked to restrain the government from mandatory textbooks. Under the motto of “autonomy of colleges”, many universities (even public universities) have successfully refused the government’s 2008-2012 drive to allow the public or private owners to handpick university presidents.

0 Comments