K.S. Park spoke at International Institute of Communications Annual Conference 2025, held in Bogota, Colombia, on October 22-23, co-hosted by the Commission for Communications Regulation of Colombia (CRC) (Executive Director Claudia Ximena Bustamante Osorio in the first selfie below) at a session titled : Open Internet and Digital Infrastructure, moderated by Prof. Konstantinos Masselos, President, Hellenic Telecommunications & Post Commission (EETT) (in the second selfie below) on the invitation of Alianza por una Internet Abierta (AIA, Open Internet Alliance; Executive Director Mercedes Aramendia in the third selfie below) . He shared South Korea’ experience of departing from the bill & keep rule and commented on the possible future scenarios of how the mandatory dispute resolution proposal envisioned in EU’s Digital Network Act will unfold, extrapolating from the Korea’s dispute resolution experience.

Question: Korea is the only country that tampered with (albeit partially) the bill and keep rule of the internet that financed to scale the data delivery cost of any-to-any communications among all the connected computers around the world. What has been the experience of Korea?

The information revolution was made possible by the bill & keep system by which no one had to pay for sending data (or even receiving data) as long as everyone pays the modest cost of maintaining connection. Now, the sender pay rule exactly undercuts the revolution by taxing people for sending traffic, which is essentially same as speaking online. For this reason, the sender pay rule proposed by telcos at ITU 2012 was roundly rejected by all stakeholders.

The fair share deal proposed again by the telcos is similar to the sender pay rule, namely making the traffic sender pay a fair share of the cost of maintaining the network that receives that traffic. In South Korea 2016, the government instituted the sender pay rule but only partially, meaning only among the telcos.

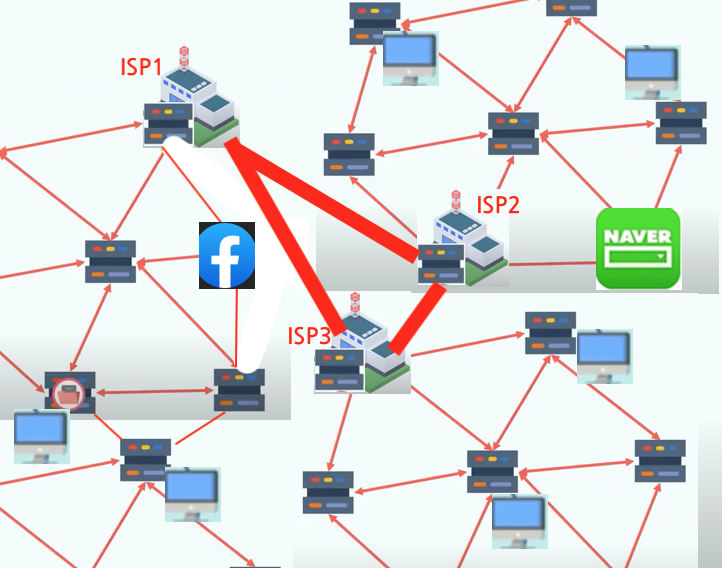

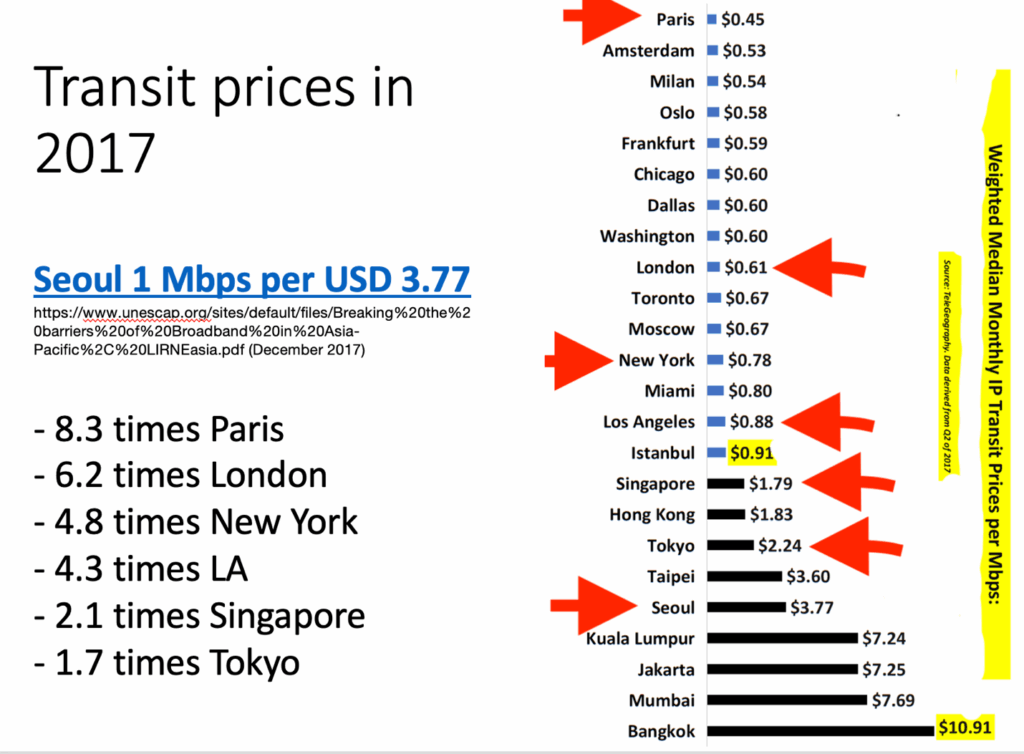

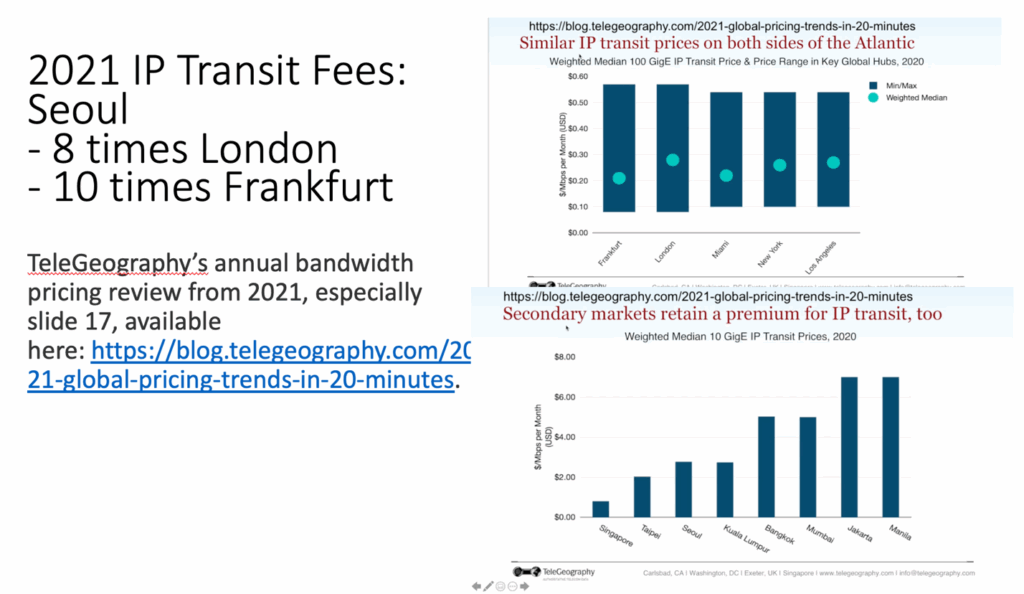

What happened? Telco hosting popular contents like Facebook (ISP1) in the picture above, by definition became the net sender of the traffic because people in ISP2 and ISP3 also pull traffic from ISP1. As a net sender, ISP1 had to pay other telcos under the sender pay rule. Faced with this financial incentive, So competition among ISPs to host popular contents disappeared. Korea became the only country that the transit prices, or the internet access fees for the content providers, did not fall unlike all other countries. As a result, in 2017, the content provider side internet access fee or in short transit became 4-5 times NY/LA or 8-10 times Paris/London.

0of%20Broadband%20in%20Asia-Pacific%2C%20LIRNEasia.pdf (accessed 13 April 2025)

-global-pricing-trends-in-20-minutes (accessed 13 April 2025)

This has made the network environment toxic for Korean content providers which explains why we don’t see many successful startups from the country since NAVER and Kakao came into the current incumbency 20 years ago. Even public interest apps like COVID19 contact tracing apps suffer from high transit fees that network fees are restricting the ability to meet the demand. The video streaming app Watcha paid 10% of their revenues as transit fees in 2021 and the video platform app Afreeca paid 2019’s entire profit as internet access fee in 2020. Many Korean content providers also ended up relocating from Korea to cheaper countries like US to avoid the exorbitant internet access fees.

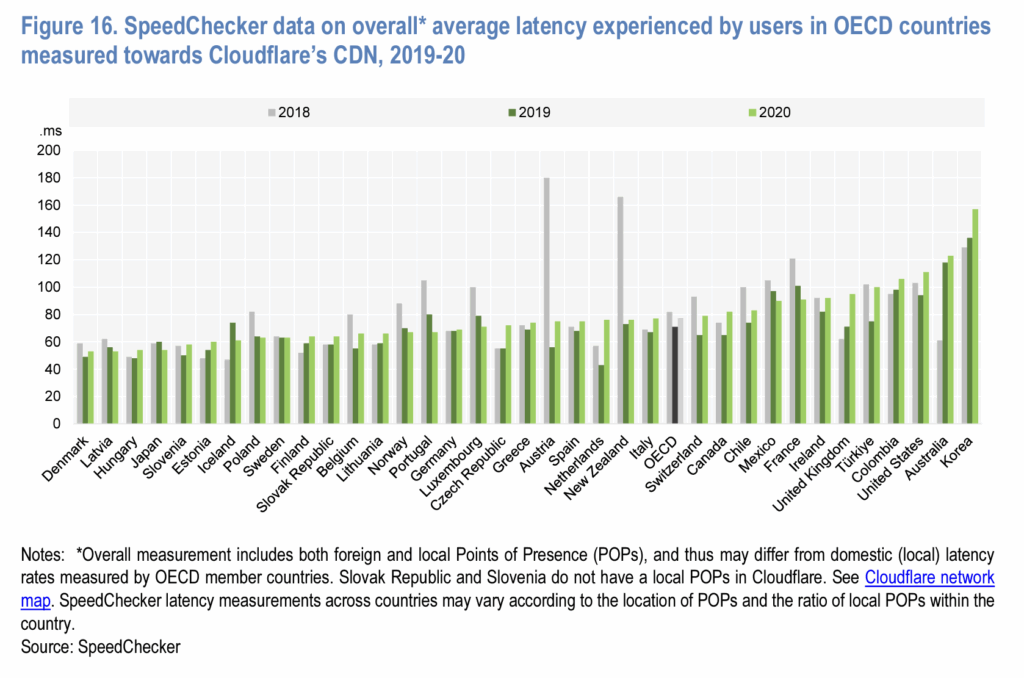

Now, when transit fee rises, peering fees rises also. High transit fees exerted an upward pressure on the paid peering fees that Korean ISPs charge on overseas content providers. As a result, Twitch the game video platform pulled out of Korea citing ‘network fees 10 times more expensive than in most other countries’. On top of that, Cloudflare gave up serving Korea content from Korea but instead serving from Hong Kong or Tokyo, making Korea the market with highest latency among OECD.

The Korean experience with the sender pay rule shows the future of the European one, which is even clearer as the law will directly incentivize ISPs to extract as much transit and peering fees as possible.

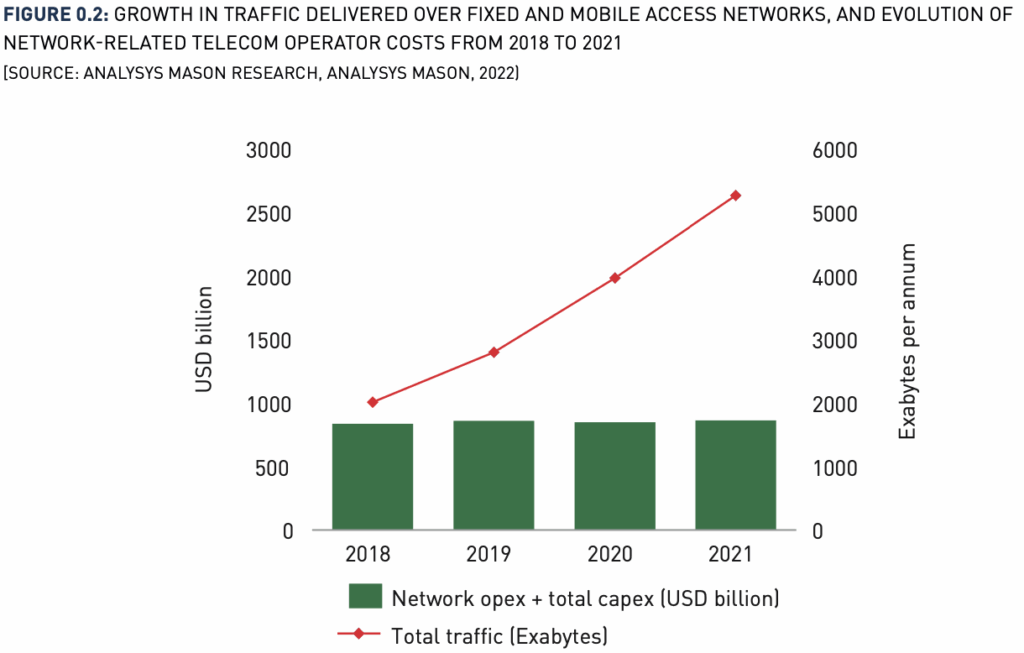

Probably, there is a nagging argument that still big techs should do something when their share is more than 40% of the entire traffic volume. The argument does not have any force. NVIDIA chips cover 90% of AI chips market. Does it mean that NVIDIA must pay some tax to the electricity since 90% of the electricity powering computers go through their chips? There has to be a substantive reason such as sending data more causes more cost. If you look at the cost of maintaining the network even including capital expenditure, it did not increase over the four years of pandemic during which the traffic increased 5 times.

ON THE ECONOMICS OF BROADBAND ISPs”, October 2022, p.33

Why? Because no matter how much traffic is passed through the pipelines, it does not create any more cost.

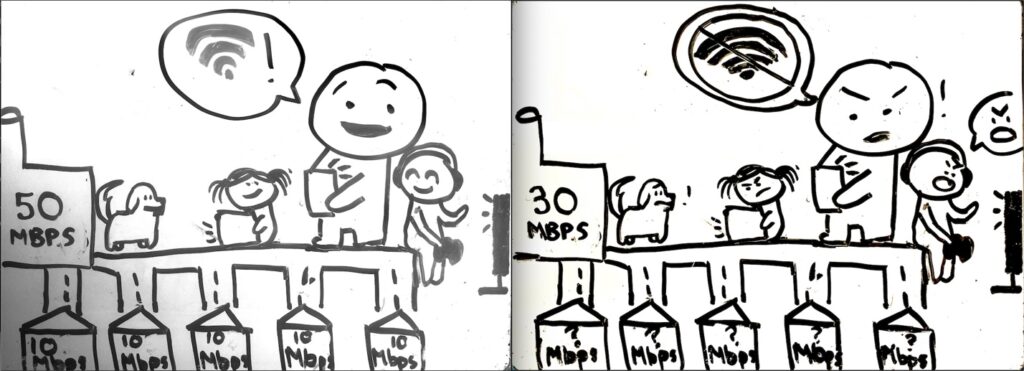

What causes a congestion on the network is when the regional capacity does not support all the bandwidths going into the houses.

Such overbooking is okay since not everyone uses the internet at the same time. But when congestion is caused, whose responsibility is that? the telcos’ failure to provide sufficient local network capacity to support the advertised bandwidth sold to each household.

Question: What is the outlook for the dispute resolution system that Europe has instituted? Is there a lesson from the Korean experience which involved actual disputes under the name of ‘network usage fee’?

Net neutrality arguably allows paid peering but the problem with the new network fee rule is that it is not just allowing paid peering but mandating it. If a law requires one party to pay and the other party to get paid, without saying how much, what do you think will happen in that relationship? It will be abused by the party entitled to payment because no matter how much they ask, the other side must succumb to it at some point because they have legal obligation to pay something.

When that happens, what is the other option for the sending party? Drop the connection. This option is not just imagined. That is what happened with the dispute KT v Facebook in South Korea. When the sender pay rule kicked in in 2017, KT was hosting Facebook’s cache server. KT realized that they are paying too much to their rival SK who has more subscribers who were pulling more data from KT’s network than the other way around, making KT the net sender. KT turned around and began to ask Facebook their customer to compensate KT for the loss. What did Facebook do? Facebook dropped the connection! Not everything but only for the data traffic requested by SK’s users. So the peering connection disappeared and everything went through the long-winded transit route. All the SK users began to suffer huge latency. Is this wrong? Korean Communication Commission intervened of course to sanction Facebook for dropping the peering connection. However, the court revoked KCC’s decision, saying that Facebook did nothing wrong! This shows that the rule mandating paid peering will just have no teeth, unless the rule will force the parties to maintain connection.

This shows the failure point of the new variation of the fair share rule, the dispute resolution rule of the EU’s Digital Network Act. The arbitrator will be in a very awkward position because he has to somehow cough up some amount without any justification for it knowing that the content providers will just drop the connection if the amount is too much.

The judge in the lawsuit between SK Broadband and Netflix in Korea was exactly in that position. SKB and Netflix were peering outside Korea because SKB, unlike its rivals KT and LGU+, refused to connect settlement-free with Netflix’s Open Connect Appliances (cache server) in Seoul and instead demanded settlement. Netflix wanted a ruling that they don’t owe anything to SKB. Netflix lost under the judge’s rule that “network is not to be used for free.” However, if you read the judgment, the court says that Netflix may satisfy the payment obligation by making their own investment into the connection, specifically mentioning their cache server network OCA as a possibility. In short, Netflix did not lose in that lawsuit because Netflix for long wanted SKB to accept the traffic through OCA. If the party was Meta, the judge would have accepted Meta’s subsea cable network as payment for Meta’s onshoring of their content into the South Korean network.

Now, most big telcos demanding fair share make a nationalistic argument, as if this is different from the sender pay rule. They are saying that they are spending money to maintain the domestic network so whoever is invading it with tsunami of data needs to pay the telcos maintaining it. What telcos are forgetting is that that cross-border traffic route has the overseas segment and the domestic segment. If they are paying for the domestic segment, who is paying for the overseas segment? Big techs are paying for that by investing in subsea cables or content delivery networks. If you weigh the distance that the data travels, Meta and Google will be the biggest telcos in the world. Telcos can charge their customers the monthly fees exactly because the customers can receive data from overseas big techs delivered through their subsea cables and CDNs. So telcos are benefitting the big techs’ overseas infrastructure just as much as big techs are benefitting from the telcos’ domestic infra. It is a mutually beneficial relationship. Actually, telcos already know this because, when they received the overseas traffic through the higher tier providers, they paid money in dong so. Now, by receiving traffic directly from big techs that deliver the traffic at the telcos’ doorstep, they are actually saving that money. It is the early internet framers’ decision not to charge one another in this mutual beneficial relationship, and namely adopt the bill and keep rule that made the information revolution possible. And this is why global civil society, despite all the platform accountability talk, want to protect big techs from being charged because they know that if platforms are charged taxes for sending traffic, that tax will trickle down to them.

Question: Does the primarily mobile nature of communication in some countries change the justification for the bill and keep rule?

Why did the Koreans tamper with the bill and keep rule whereby everyone pays to connect so nobody pays to send, and which began the information revolution?

They thought that more and more people will use internet through mobile and there has to be proportional charge for people using the network. Most mobile users pay not just flat connection fees but also for data usage already so why not apply the same rule for wired internet?

What they didn’t realize was, firstly, users do not pay to send, they usually pay to receive data. So there is no reason to charge the senders upstream. Secondly, the reason that telcos are charging for data usage is not for the usage of their wired network but for the usage of their proprietary mobile network. Mobile networks are exclusively built by respective telcos and they do not connect to other mobile networks, at least not through mobile networks. It is the main servers of the mobile networks that connect to one another and other autonomous systems through the wired internet. There is no mutual beneficial relationship found between wired internet networks. They can afford to charge for use of their proprietary mobile network in a receiver-pay rule or without data cap or whichever way they should. This should not change the bill and keep rule governing the internet connection.

________________________________________________

Introduction

This panel will discuss the importance of the open, decentralised architecture of the internet as the foundation of innovation and global connectivity.

- Complementary roles of telecom operators and technology companies, each investing in different layers of infrastructure

- Assessing the need for state intervention in complementary private network infrastructures (such as CDNs, data centers, and submarine cables)

- Preserving open peering arrangements that sustain efficient data flows worldwide

- The role of civil society, academia, and regulators in multistakeholder governance, focusing on concrete case studies

- Ensuring the future of digital infrastructure remains aligned with the values of openness, resilience, and accessibility

Moderator

Prof. Konstantinos Masselos, President, Hellenic Telecommunications & Post Commission (EETT); Board Director, International Institute of Communications

Speakers

Ana Luiza Valadares, Public Policy Director, Connectivity, Infra & Devices, Latam – Meta

Cristiane Sanches, Leader of the Board of Directors, Brazilian Association of Internet and Telecom Providers (Abrint)

Raquel Rennó Nunes, PhD, Senior Programme Officer, Article 19

Kyung-Sin Park, Professor, Korea University; Director, Open Net

Lina María Duque del Vecchio, Communications Commissioner, Commission for Communications Regulation of Colombia (CRC)

0 Comments